The Upper Raritan River watershed region is known for its scenic countryside – rivers, streams, forests, farms, and villages – but that doesn’t mean residents are free from the threat of chemical contaminants in our drinking water supplies.

An emerging contaminant of concern is the group of chemicals known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS for short.

PFAS contamination isn’t limited to industrial sites—it has been detected in private wells across New Jersey, raising serious concerns about groundwater pollution and public health. These “forever chemicals” enter drinking water sources through various pathways, including industrial discharges, landfill runoff, and the land application of “biosolids,” the treated sewage sludge used as fertilizer on farm fields.

PFAS are becoming ubiquitous in the environment. These compounds have been found in urban, industrial, suburban, rural, and agricultural areas. Because they take forever to break down, they accumulate over time and increase in concentration.

Exposure to PFAS has been linked to numerous health problems, including certain cancers, birth defects, hypertension in pregnant women, and weakened immune systems. These chemicals have been widely used in consumer products such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, water-repellent clothing, firefighting foams, and microwave popcorn bags.

Raritan Headwaters has played a crucial role in addressing PFAS contamination by quickly informing residents, providing well testing resources, and advocating for solutions—helping communities protect themselves while waiting for broader policy changes.

A Rapid Response to Impacted Communities

While state and federal agencies often take years to address environmental threats, organizations like Raritan Headwaters are on the front lines and can mobilize quickly to help affected communities.

For example, when Hunterdon County residents, near the border of Lambertville and West Amwell, discovered potential PFAS contamination in their private wells last summer, they turned to RHA for assistance.

We tested 29 homes in that neighborhood so residents could learn what’s in their water and make informed decisions. PFAS contamination was detected in 28 of the 29 wells initially tested.

The investigation has since expanded, with the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) joining last fall. Additional well testing is ongoing, and residents may qualify for grants from the DEP’s Spill Compensation Fund to install water treatment systems.

The source of the contamination remains under investigation. Potential sources include a former electronics manufacturing site, where PFAS was used as a product coating, and the former City Landfill—an unlined landfill that lacked a DEP closure plan, remediation, or capping. Dumping continued in and around the landfill for years, and officials have yet to determine its full size or the extent of contamination.

How PFAS Gets Into Groundwater

A recent New York Times investigation revealed that sewage sludge with high PFAS levels continues to be used in agriculture—despite decades-old warnings from chemical company 3M. The biosolids allow PFAS chemicals to enter the human food chain through contaminated crops and livestock.

The Times article, part of a series on PFAS in agriculture, cited reports from the early 2000s by 3M scientists. In a 2003 meeting, they warned the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) about high PFAS levels in sewage. However, no action followed, and the data remained buried in EPA archives until recently.

As a result, PFAS continues to contaminate groundwater and rivers that supply drinking water, posing a significant public health risk. Human exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) primarily stems from polluted water, food, industrial waste, and consumer products.

Immediate Action Needed: Stronger PFAS Regulations

Maine is the only state that fully bans PFAS-contaminated biosolids from land application. While New Jersey was an early adopter of strict drinking water standards for PFAS, the state is still developing regulations to address PFAS in water, soil, and air. In 2022, the state passed the “Protecting Against Forever Chemicals Act,” which restricts PFAS in products and enhances monitoring.

Earlier this month, the U.S. EPA released a draft risk assessment on two specific compounds in sewage sludge, PFOA and PFOS, for public comment, signaling growing federal concern. However, challenges persist, including limited testing capacity and continued contamination from consumer goods.

In New Jersey, about 12% of sewage sludge is still used as fertilizer and topsoil, with 1% applied directly to farm fields for animal feed crops. Without stricter state and federal regulations, PFAS will continue to infiltrate water supplies, making mitigation efforts increasingly difficult.

The links between PFAS chemicals and cancer and other serious health issues underscore the urgent need for stronger policies. RHA urges state and federal agencies to take decisive action, including bans on contaminated biosolids and stricter limits on industrial PFAS discharges.

Get Your Well Tested!

The growing public concern over PFAS chemicals highlights the importance of getting well water tested for a range of potential contaminants.

Eighty percent of homes in the Upper Raritan River watershed in Hunterdon, Somerset and Morris counties – about 60,000 households – get their drinking water from privately-owned wells.

If you own a private well, there’s no way to know what’s in your water until you have it tested. Many common water contaminants lack smell, taste, or visible characteristics, so you can’t tell just by sniffing, tasting or looking at it. Municipalities and other public agencies don’t test private wells; that is the sole responsibility of property owners.

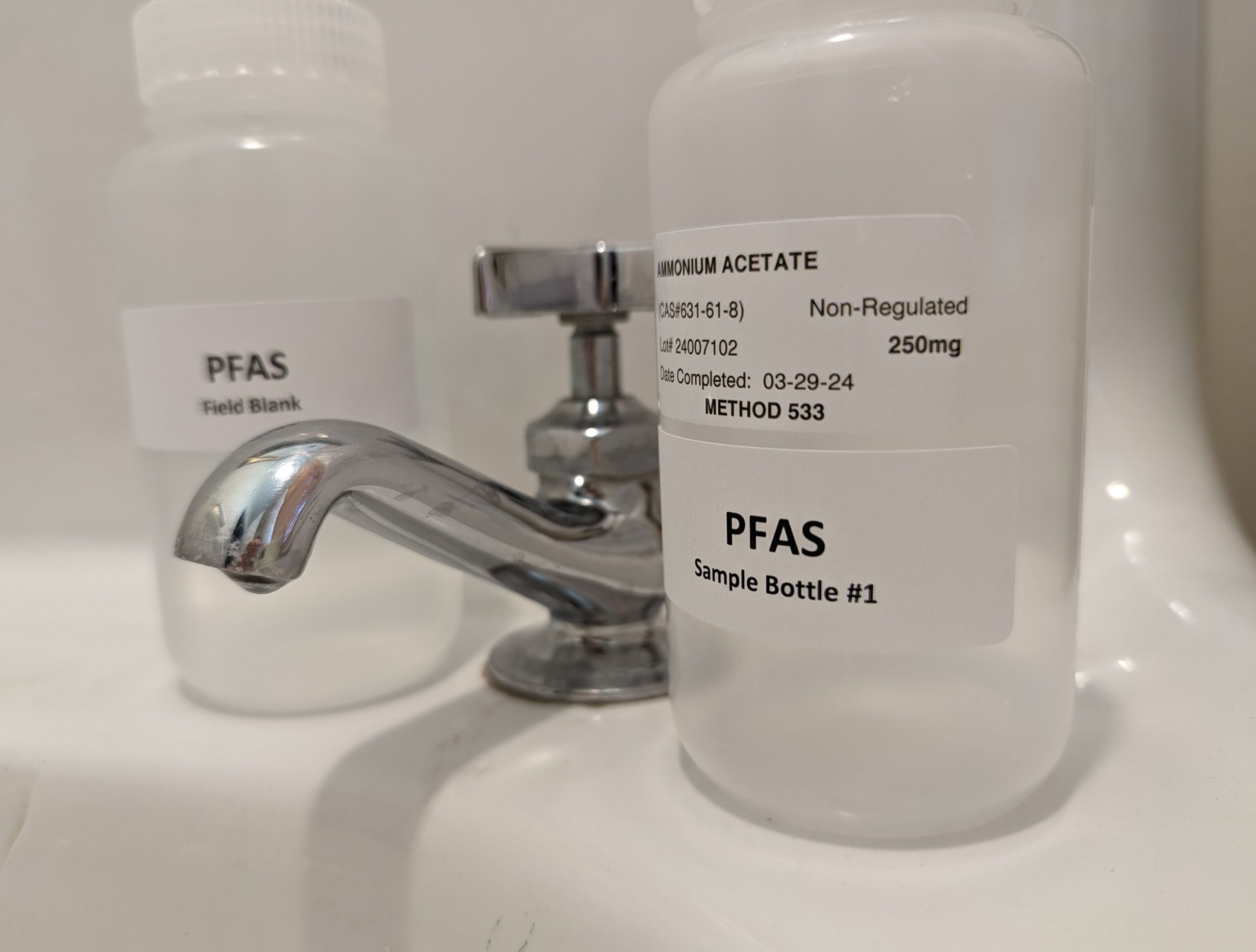

An increasing number of well owners are testing for PFAS. In 2024, 183 residents tested for PFAS through RHA’s Well Testing Program; an increase of over twice as many PFAS tests conducted compared to 2022. This testing is proving to be vital because over three years, 74% of the 404 total tested wells contained PFAS, with 54% exceeding EPA limits.

RHA currently tests for twenty-five PFAS compounds, including PFOA and PFOS, which were classified as hazardous substances under the Superfund law last summer. Testing kits are available year-round at RHA’s Bedminster and Flemington offices. Additionally, RHA hosts Community Well Testing events in the spring and fall to increase accessibility. To learn more about PFAS and access resources on testing and treatment, explore the new PFAS Toolkit on RHA’s website. To learn more or purchase a test kit, visit www.testmywell.org. For your health and safety—if you have a well, get your water tested!